Out of Turbulence, Communities Re-align Across the City

By Tommy Wang Zilong

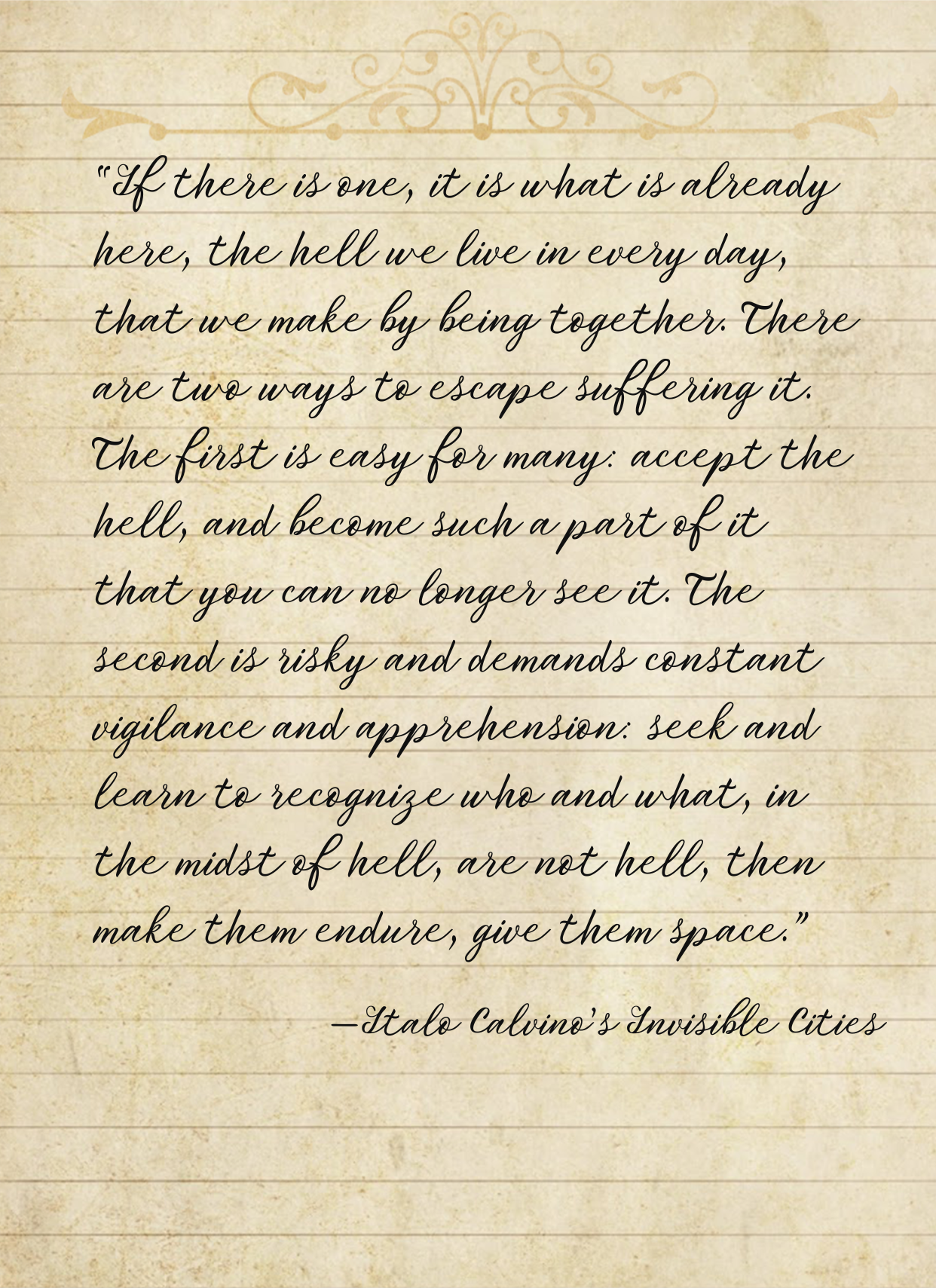

Benjamin Sin’s credo rings around an independent bookshop at a public sharing session in Wan Chai. He is citing Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities.

“It’s like we’re wandering through hell, looking for who and what doesn’t belong. Finding people and stories that are alive and then passing them on, making them endure, giving them space. It’s the little bits of life that make this place a resilient community.”

A registered social worker, Sin believes that, in a city with an increasingly limited political system, it is the social actors, the people who want to document and affect change, that are building an ‘invisible’ Hong Kong.

The fabric of Hong Kong society has changed so thoroughly over the last few years that, even to locals, the city now feels somewhat foreign.

According to the Department of Census and Statistics, Hong Kong’s resident population dropped to 7,332,000 at the end of 2022, a decline of nearly 150,000 from mid-2020, when the new National Security Law (NSL) came into force.

Along with the new NSL, COVID-19, social unrest and a former police officer elected as Chief Executive in a general election that saw the lowest voter turnout in Hong Kong’s history, have all contributed to four tumultuous years in the city.

“There is a sense of disenchantment in Hong Kong’s civil society, but there is nothing to do about it. To feel that we have no hope in the present is like accepting hell and becoming part of it,” Sin wrote in a contribution to a book on the preservation of Pok Fu Lam Village, one of the oldest villages in Hong Kong. The book was published in 2018, before the turbulence of the years to come. “But this is also a very important life lesson from God,” he wrote.

A community survey conducted by Hong Kong Youth Epidemiological Study (HK-YES) on the mental health of young Hong Kongers, in 2020, revealed that 14.7% of young people suffer from depression. This is reportedly three to four times the rate in Japan, South Korea and Mainland China.

A year later, a study conducted by the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Hong Kong, found that 40.9% of the 100,000 people surveyed had moderate to high levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSD). Nearly 73.7% had moderate to severe depression, and 36% had symptoms of both.

But, as wounds heal, a spirit of community, identity and resilience seems to be taking root amongst those residents who have chosen to stay.

Creating Community Connections

Sin is a senior social work supervisor at Caritas Hong Kong, a non-profit organisation that provides services to communities across the city. One such service, set up by Sin and his team before the COVID pandemic, was the Healthy Neighbourhood Kitchen Project.

The project brings together thousands of people living in subdivided apartments across the central, western and southern districts of Hong Kong Island, providing a communal space for them to cook and network, rather than allowing them to contend with a lack of space and time, on their own.

A second project hatched by Sin’s team during the COVID-19 pandemic, Buffer Space for Families in Urgent Housing Crisis, provides short-term housing for those suffering from housing instability and unemployment, by utilising vacancies in hotels and hostels.

Both projects continued to operate through the pandemic, despite numerous barriers, and are still ongoing.

“[Often] we just use the facilities in public spaces to enhance the living conditions of people, and to help them get out of a bad situation,” said Sin in the sharing session, in March 2023.

“In the relatively affluent Central and Western District, we see that there are more than 3,000 residents living in coffin homes [otherwise known as subdivided apartments] that you don’t see,” said Caritas’s volunteer May Huang in an over-the-phone interview. “As a participant [in these projects], my belief is that social work is a life-impacting process. The work that empowers social groups can lead to change and sustainability.”

As a Mainland Chinese student studying social work at the University of Hong Kong, these volunteer activities have helped Huang build trust and foster connections with local groups.

“It’s a ‘how-to-fish’ way of teaching [the same idea as, if you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime]. It makes you happy to see people at the bottom of the social ladder, whose lives have been improved by your help, and who have gained access to more social resources,” she said.

Sin’s Neighbourhood Kitchen gathers locals living in coffin homes a space to gather on weekends. (Source: Neiborhood Kitchen FaceBook)

These experiences have made Huang want to stay in Hong Kong and keep serving the local community. The work has given her meaning.

“It’s a ‘how-to-fish’ way of teaching [the same idea as, if you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime]. It makes you happy to see people at the bottom of the social ladder, whose lives have been improved by your help, and who have gained access to more social resources,” she said.

When in doubt, walk about

“I brought you here, not because there is anything special, but simply for you to see it,” urbanist Sampson Wong raises his voice to a group of volunteers, urging them to squeeze into an unassuming space of less than three square metres, between a Mong Kok MTR exit and the adjacent building.

Wong guides volunteers through Mongkok to show how “walking” has inspired him in recent years.

“Once we discover a space, it seems to take a meaning,” Wong said in the scheduled walk.

He is promoting his philosophy of “strollism”, which he first started in 2020 via his YouTube channel. During the pandemic, Wong began a series of videos named, “When in Doubt, Take a Walk”, in which he encourages viewers to walk around Hong Kong’s urban spaces, merely for pleasure. In doing so, he hopes people can find appreciation in the sometimes-hidden details of their neighbourhood.

He wants Hong Kongers to find solace in the chaos of urban life by taking photos and writing down what feels memorable and inspiring.

Wong’s ‘When in Doubt, Take a Walk” YouTube channel. (Source: YouTube)

In 2022, Wong published his book, Hong Kong Strollism (香港散步學) in which he recounts ten routes around Hong Kong streets and 100 spaces to discover in the city.

Wong was approached by Taylor Lee in early 2023, of the Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association of Hong Kong (YMCA), to help young people involved in an urban change project specifically centred around the Yau Ma Tei area. This is what brought Wong and his group of volunteers to the Mong Kok MTR exit in March 2023.

Wong on a stroll near a busy Hong Kong intersection. (Source: Sampson Wong)

“When we walk around armed with questions, we open our five senses to perceive. We want to try to see how we can inspire, and then to help people with their daily problems,” says Lee, explaining the project’s objectives. “We often think about how to serve our young generation and what help we should give them. They need to know how to take care of and love the city.”

“[Walking] is a way of connecting with the city. Sweat and footsteps have been our way of communicating with it.”

Transforming urban spaces through placemaking

If strolling is the starting point, then for architect Sarah Mui, the challenge is to inspire Hong Kong’s youth to create and innovate.

“It might be the right time to better use our knowledge to tackle needs with resources. Everyone deserves a better city and world, that’s what I’m trying to believe in,” said Mui during a volunteer workshop. For two months, she trained volunteers to transform the old Yau Tsim Mong district, which incorporates areas such as Yau Ma Tei and Mong Kok.

Mui with volunteers at a workshop about placemaking.

According to a study by the Urban Renewal Authority, 80% of the buildings in Yau Ma Tei and Mong Kok will be over 70 years old by 2047. Another report, issued by think tank Civic Exchange, shows that Yau Ma Tei is one of the 57 districts in Hong Kong with the least amount of open space.

“I need you to find a problem that needs solving, identify those affected by that problem and then find ways to address it,” Mui told the volunteers.

Placemaking is a term Mui aptly uses to describe her work, referring to the process of transforming urban spaces into places that reflect and enhance the communities that use them.

“We don’t necessarily want the city we see to be easily changed. We want to create by ourselves,” said Mui. “I hope more and more people will get involved and be part of shaping the future, slowly sowing the seeds of the city we want.”

“[If so] we will be rewarded in the end.”

Mui and her team believe it is unrealistic to rely on Hong Kong’s youth to transform ageing districts over a short period of time. For now, it is important to engage young people, in order for them to then build the city of their dreams.

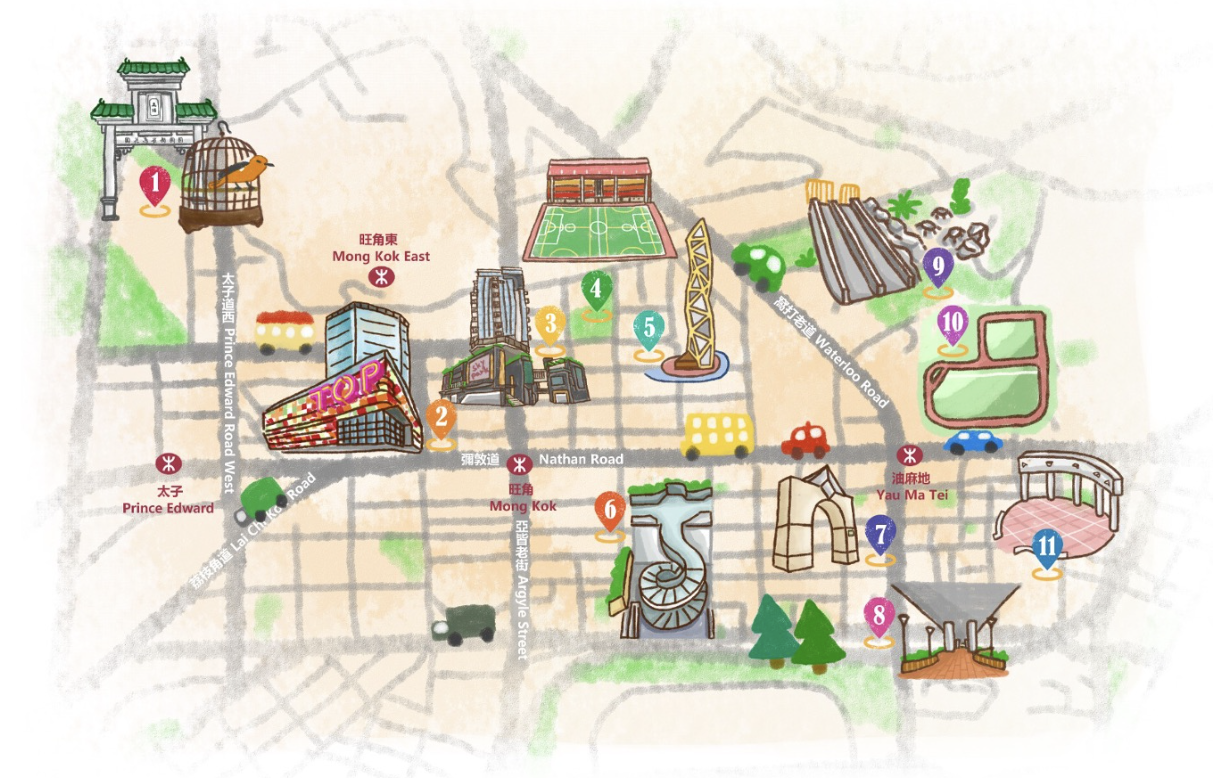

A team of three volunteers from Mui’s workshop were inspired to create a map of over a dozen ‘less-visible’ public spaces around Prince Edward, Mong Kok and Yau Ma Tei MTR stations. The volunteers discovered that locals were dissatisfied with a lack of quiet public spaces to rest and relax. By making and distributing the map, the volunteers hoped to give more exposure to these sites.

“The designs are low-cost, but we see the seeds of creativity responding to real problems we encounter in our lives,” said Mui. “We started planning the project by thinking, what should we do to give our youth more motivation to walk and discover, and show more care and love for the city?”

Map to promote ‘open’ public spaces in Mong Kok district by volunteers. (Source: Shirley Wong)

“I saw the urgency of the transformation and I believe this is some kind of responsibility for my future,” Ian Chan said in a phone call interview.

“It’s infectious. It made me feel like I need to get involved soon in finding hope for building lovely places.”

In an episode of the Japanese manga series Keroro Gunso, characters plant flowers all over earth in order to “invade the human world.” Mui remembers loving this episode.

“Like the animation, I hope that more people will unconsciously participate in placemaking and be a part of the city,” said Mui. “In that way, change is not a difficult task. By slowly sowing the seeds of the desired city, we will reap the rewards.”

“No matter how rigid the rules of the system are, people are alive,” Mui said.

Mui is also the Co-Founder & Design Director of Onebite Design and is known for her organic blend of humanistic care and community architecture. In 2021, she was responsible for the design of Ming Tak Sports Court, described as the first ‘girls-prioritised’ basketball court in Hong Kong. The site was reportedly welcomed by gender equality and women’s rights group.

Basketball players engage in a game at Ming Tak Sports Court in Tseung Kwan O backdropped by mural that says “Tomorrow is Yours”. (Source: OneBiteDesign)

“It’s very difficult to make changes at the government level. It often takes half a century or more to transform ageing areas because governments lack the motivation to put in the effort,” said Maggie Wu of the Planning Department. She is also a practice consultant for Mui’s volunteer project. “But the efforts of these young people, even if they are tiny, can be rewarding.”

“So what if some leave? So what if some stay? More are leaving, but currently, no matter what choice I make, I feel helpless,” Maggie Wu exclaims. “Definitely, Hong Kong is not the same anymore, but you never know what the impact of what we’re doing now will be.”

Invisible Hong Kong

For Benjamin Sin, Calvino’s Invisible City is neighbourhood-based resilience that we can see in Hong Kong communities today.

“We still have to be humble, to see the people in our community and serve our fellow man,” Sin says.

He deems the effort is about rebuilding a sense of identity.

Sin’s favourite passage from Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. (Source: Agnes Wang)

“It’s been a couple of difficult years,” Sarah Mui holds a similar notion. “However, there are real and urgent daily needs from citizens that are independent from the socio-political environment. These needs are directly related to the well-being and social resilience of the city.”

“Many are in different fields and positions, but they all seem to be led by a certain thread, doing similar things to Benjamin, Sarah and I,” Sampson Wong said of his observations on Hong Kong’s civil society over years. “The thread is we must strengthen our connection to communities and strengthen our resilience.”

Wong talks with workshop participants in Sai Ying Pun. (Source: Sampson Wong)

“In this era of diaspora, I want to respond to the emotional needs of Hong Kong people. In the time to come, how we tell our story and express our love is likely to rebuild a sense of spiritual belonging and it embodies a place and architectural space,” he continued.

“That’s the responsibility I’m determined to keep.”

Extra Credits

Advisor Keith Richburg

Editorial Director Hailey Yip

Multimedia Director Madeleine Mak

Multimedia Producer Larissa Gao

Illustrator Agnes Wang & Jamie Clarke

Copy Editor Jamie Clarke

Fact Checker Olivia Guan