Six Feet Under

Hong Kong Funeral Directors: Finding Meaning in Life and Death

By Ma Yun, Sylvia

Thank you, Mr. Chung. I think I can finally let go of my brother’s death. Thanks for being with us all these years.”

The unexpected phone call came this March from a female client of Lok Chung, who runs Peace of Mind Funeral Services in Chai Wan. The client’s brother had committed suicide more than ten years ago. Chung helped arrange his funeral.

Chung has kept in touch with her – one of his earliest clients – ever since, even offering consolation when needed. She struggled to move on from her brother’s premature death.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Chung made arrangements for her brother’s bones to be relocated from his grave in Hong Kong to their ancestral home in the Guangdong province of China. However, when the pandemic hit Hong Kong, the ashes couldn’t be delivered to the mainland until the reopening of the borders, so they remained in Chung’s office for almost three years. The phone call came after the client’s family could finally take the young man’s ashes back to their ancestral home, in early 2023.

Chung was choked up. Though it is of professional practice to “wear a mask” when facing his clients, he admits that this detached approach is something he has yet to master, even after over ten years in the funeral industry. “This job brings about a lot of emotions in me, behind the mask,” Chung said.

Experiences like this cemented his commitment to this line of work. “This makes me believe that I am doing something meaningful,” he said.

“It’s now more than just an ordinary job, more than just making a living; it has evolved into something bigger – I have a strong sense of mission about my work.”

A Taboo Topic in Hong Kong

Chung, 38, is running one of Hong Kong’s 136 licensed burial catering companies in the funeral services industry, according to data from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department.

As a funeral director, Chung’s job covers almost all aspects related to what happens after a person has died. Those include processing formal documents, booking of a hearse, applying make-up to the deceased, and arranging the funeral.

Infographic by Agnes Wang.

Death and mourning are a phenomenon that never induces easy conversations anywhere, and especially in Hong Kong, it remains a cultural taboo that should avoided if possible.

In Cantonese, euphemisms are often used in replacement of the word “death”, such as “walk away” zau2 zo2 or “go away” heoi3 zo2. Not only do people avoid speaking of “death”, they even shun the word’s homonyms. The word “four” sei3 in Cantonese sounds similar to the word “death” sei2 and is therefore considered inauspicious. Because of this, some buildings do not have the 4th or 14th floor, and some traditional wedding receptions do not even have a “table 4”.

“The funeral industry was much looked down upon in the past,” Chung said. “People knew little of us, so they were afraid of us.”

People handling matters around death are considered ominous. Chung said some elderly people even lashed out at him when receiving his business card, thinking Chung was cursing them to die sooner.

“The concept of the ‘funeral director’ has only recently emerged in Hong Kong. People used to call us ‘coffin men’ and even ‘coffin rats’,” he added.

Funeral directors, whose daily work concerns death, may have joined the industry for a variety of different reasons, but what keeps them all going on the path is similar – a sense of meaning embedded in the profession.

“Fulfil My Need for Meaning”

The urge to have a radical career change hit him one ordinary day, when he returned from his lunch break to his colleagues chatting about food and movies, as usual.

“It suddenly occurred to me that this was not what I would want to be doing some 30 or 40 years down the road,” Chen, now 30, said. “I’d like to do something more meaningful.”

His family, which he described as “very traditional”, initially opposed his plan to go into the funeral business, calling it “ominous” and “unsanitary”. Then after witnessing his devotion to helping arrange his grandfather’s funeral, in August 2022, they started to appreciate the craft and eventually accepted his decision.

Compared to his previous job in teaching, funeral planning is more creative, Chen said. He puts a lot of effort in designing and refining details of the funeral process to make the experience more meaningful for the grieving family. Sometimes he will ask family members to put on the shoes for the deceased, to express “their final filial piety to the deceased and a wish for them a good journey to the other world”.

Chen said he’d never looked back since he committed himself to the death-processing profession four years ago. When asked if he would still choose this path if he could go back in time, he said he would still make the same choice again.

“I can’t imagine what else I would do if I weren’t a funeral director, or a life and death educator,” he said. “The job fulfils my need for meaning, and I happen to have what it takes for it – the ability and the energy.”

Family Business

Handling the dead is perceived as such an unconventional profession in Hong Kong that even Chung, whose family have run the funeral services for decades, faced domestic opposition when he started out.

As someone who had studied and received a business degree in Australia, Chung did not initially expect to enter the industry so early in his 20s.

But when he returned to Hong Kong, after graduating in 2009, the city was reeling from the Global Financial Crisis, and the company he worked for went under. He decided to help out with the family business as a transition before his next job.

To Chung’s relatives, including his mother, his decision to manage funerals was a waste of the time and money he had invested in studying abroad.

Lok Chung runs his own funeral company and takes apprentices. (Credit: Ma Yun, Sylvia)

For a long time, Chung’s family could not understand his commitment to the profession, despite the fact they had been in the funeral industry since his grandfather’s generation.

It was also Chung’s early experiences in helping the family business that have fostered his interest in funeral services. Every summer since middle school, he would assist his father and uncle in some funeral procedures.

“I’ll never forget the first time I went to a cemetery to help collect the bones of the deceased,” said Chung, referring to one of the steps taken in Chinese culture to relocate the dead’s remains.

“When the lid of the coffin was lifted, I saw the skull of the deceased. It was light brown and lovely. I thought I would be scared, but I wasn’t at all. I just found it intriguing.”

As he spent more time in the industry, what had initially been considered a transitional job has now become Chung’s true calling. The anthropological aspect of the profession has greatly engaged his curiosity and sustained his interest.

“Every aspect of our job is about people, whether it’s the dead or the living (their families). This is our shared humanity, no matter how your background differs.”

“The more funeral services I do, the more I realise there’s so much to discover behind it, and the more I enjoy the job,” he said.

No Longer Fearing Death

Hazel Yu, a former senior administrative staff at an approved trustee for the Mandatory Provident Fund, said she had never thought she would be connected to the funeral industry.

Though her previous job also involved processing the documentation of “deaths”, she had never thought of “working in such close contact with death,” as someone helping the families of the deceased prepare for their funerals.

Last year, however, the sudden death of a friend’s husband shocked her greatly. “For the first time, I realised death was so close to me,” this 50-year-old woman said, sighing.

As a single mother, Yu suddenly felt a strong urge to spend more time with her daughter, finding that her previous hectic work schedule was impeding these efforts.

“While my friend was so busy with her husband’s funeral, I couldn’t do anything to help her,” she said with regret. The frustration spurred her to learn more about funerals, with the hope of helping friends with the funerals of their loved ones, if necessary.

She quit the administrative job she had been working for nine years and started learning under Chung to be a funeral director. She has now been in the industry for about half a year.

For Yu, the funeral director is like a “lifeguard in a swimming pool”, who needs to keep an eye on everything happening at the funeral and handle any unexpected situations. But despite the work pressure, the job also provides her with a deeper sense of life and death.

“Mr. Chung often encouraged me to attend funerals more often. He said there’s a lot to learn. That’s true,” Yu said.

After seeing countless broken-hearts at funerals and people who could not even shed tears from the pain, Yu now considers it a “blessing” to have someone grieving so much over their loss.

She said she decided to dedicate her remaining working years to preparing the last journey for others.

“Now, I no longer fear death,” she said. “I know even if I passed away, Mr. Chung could arrange my funeral very well. He is my goal in being a funeral director.”

Leaving with Dignity

Au-Yeung Ka-yiu, 42, an employee at Peace of Mind Funeral Services and one of Chung’s apprentices, joined the industry in 2021 after working as a taxi driver for 10 years.

Au-Yeung, the driver-turned funeral director, says he has never been afraid of dead bodies since his first day in the business. (Credit: Ma Yun, Sylvia)

The COVID-19 pandemic hit his taxi service hard. Au-Yeung finished some work days with only one or two hundred Hong Kong dollars a day, which barely supported his livelihood in the city, driving him to change his job.

As Au-Yeung’s wife was doing some clerical work in a funeral company, he planned to get a temporary job in the industry, and then return to taxi driving when business improved.

“But now I think I won’t go back to driving the taxi,” he said, “I’ll stay in the funeral industry, if I can. This job brings me meaning that driving a cab doesn’t.”

He said he gained “a sense of meaning and responsibility” through helping the deceased with their most significant journey, and comforting grieving family members by helping their loved ones “leave with dignity”.

Like Chung, Au-Yeung said he had never been afraid of dead bodies. He can still remember his first day in the business when his colleague took him to the morgue and told him to hold the hand of a corpse.

“I wasn’t afraid at all,” he said.

“I only felt the touch of cold. It used to be the same human being as me.”

The interview with Au-Yeung took place at Diamond Hill Crematorium, one of his regular workplaces. When visiting the Garden of Remembrance in the crematorium, where the white ashes of the deceased are scattered on the ground, he bowed with folded hands, as a sign of respect, and then turned to explain the different types of burials in Hong Kong adeptly.

Explore the Diamond Hill Crematorium.

For Au-Yeung, the sense of responsibility that inspired him to continue down this path has also become a source of pressure.

“A funeral is a once-in-a-lifetime event for a person,” Au-Yeung said. “You can’t make mistakes. Your mistake will leave their family with regrets, and that can’t be reversed.”

A Greater Sense of Urgency under COVID

Towards the start of 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Hong Kong with its strongest wave, due to the highly transmissible Omicron variant. Statistics from the Department of Health and the Hospital Authority show that 13,120 people lost their lives to the COVID-19 infection from the start of the fifth wave to the end of January this year. Over 9, 200 of those deaths were people aged 80 and over.

At the peak of the fifth wave, March 2022, the city was seeing over 200 COVID-related deaths per day, and the surge in deaths piled pressure on the work of funeral directors.

Coffin supply in Hong Kong at an all-time low at the peak of COVID-19. (Credit: Ben Marans/SOPA Images/LightRocket, Getty Images)

Au-Yeung said that at the pandemic’s peak, the number of funerals they were processing daily went from one or two to as many as four-per-day.

“Some people who have been in the business for 20 to 30 years said they hadn’t seen a situation as tough as last year,” he said.

The soaring death toll also tested the city’s funeral facilities, with coffins and hearses in short supply and crematoriums fully booked. The long waits for cremation led to overloaded morgues, with many bodies smelling and peeling by the time they were cremated.

In order to prevent COVID-19 transmission, the bodies of those who had died from the virus could not be cleaned or made up by funeral directors. Heartbreakingly, family members could not have a face-to-face farewell with those they were grieving for.

Au-Yeung said they were only allowed to open the outer layer of body bags so that families could confirm the corpse’s identity through an inner transparent layer. Then, the body would be taken directly to the crematorium in a coffin along with the bag.

“We wouldn’t do anything else, and we couldn’t do anything else,” Au-Yeung lamented.

He added that many families were so distressed by this hasty process that some even wept directly over the coffin, crying that they were useless and had failed to let their loved ones leave this life with dignity.

For Au-Yeung, the sense of responsibility that inspired him to continue down this path has also become a source of pressure.

“A funeral is a once-in-a-lifetime event for a person,” Au-Yeung said. “You can’t make mistakes. Your mistake will leave their family with regrets, and that can’t be reversed.”

“I felt terrible about it,” Au-Yeung said.

“It might sound disrespectful, but I felt like I was handling a piece of trash, not a dignified person. A person’s last journey shouldn’t be like this.”

The intense work during the pandemic nearly made Au-Yeung “indifferent” to death at one point. “I even wondered if I would shed tears if my parents left one day,” he said in self-ridicule.

This situation lasted until last August, when an old friend of his passed away due to illness and Au-Yeung did his makeup as the funeral director. Au-Yeung realised that he would still anguish over the loss of family and friends.

“That pain is a completely different feeling than dealing with other remains,” he said, crediting his friend with saving him from “becoming a robot who doesn’t know how to grieve or be considerate”. “But the cost of this insight was large,” he sighed.

An Education on Death

Chen, the schoolteacher-turned-funeral director at Courtesy Funeral Planning, experienced a similar level of intensity during the pandemic. He said that he barely had time to sleep at his busiest and could only doze off in the car. The stress led to hair shedding and even the development a bald patch.

His frequent contact with death made Chen more introspective during the pandemic, giving him a deeper understanding of the relationship between life and death.

“I am now more aware of my parents’ ageing,” he said. “Many people wanted to spend cherished moments with their loved ones but couldn’t anymore. When our loved ones die, they are really gone from us.”

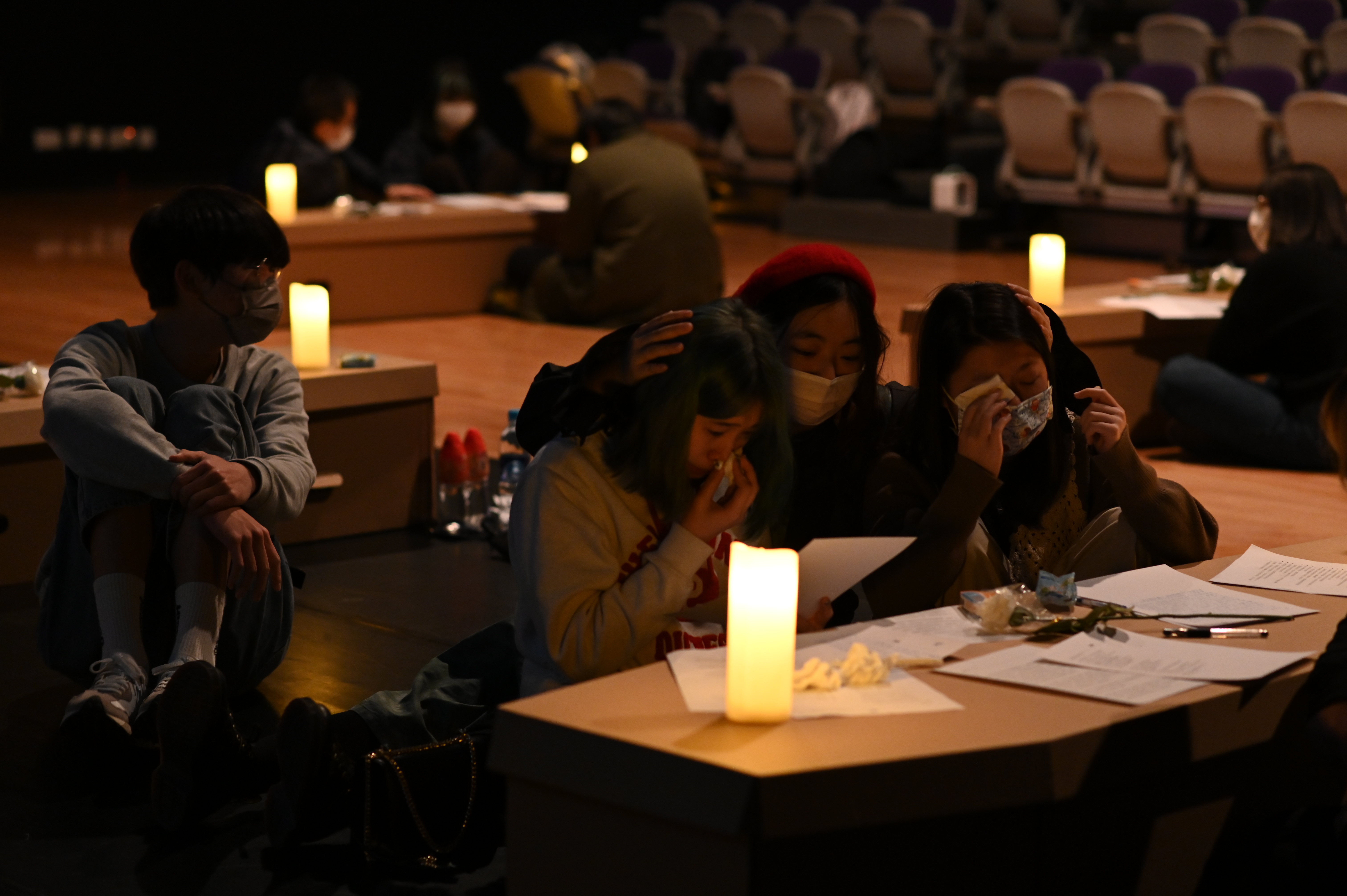

Photo gallery of Life and Death workshop. (Credit: Chen Pui-hing, HOBBYHK)

In 2018, Chen and his friends founded HOBBYHK, a youth education organisation that provides teaching programs in four fields, life and death, astronomy, ecology, and arts and crafts.

Chen is responsible for the life and death program. In his workshops, where he employs various novel forms, participants take part in activities such as guided reading of posthumous letters, a day of experiencing a funeral director’s job, and the simulation of end-of-life experience, which includes composing their own epitaph and lying in a coffin for a deep introspection.

Chen saw his two roles as complementary to one another. “I can incorporate my experience as a funeral director into death education. It’s a good inspiration for students.”

Chung, the funeral director working in the industry for over a decade, acknowledges that the social perception of the funeral industry is gradually improving in Hong Kong.

He has been invited to give lectures at universities on death and funeral culture, and is even writing a book on the history of funerals in Hong Kong. A funeral guidebook for Christians in Hong Kong, which he intends to co-author with a local priest, is also on his agenda.

Funeral directors need to master the funeral traditions in different religions. (Credit: Ma Yun, Sylvia)

“People are now more willing to learn about the industry,” Chung said. He has received a number of media interviews in recent years, which he described as “almost unheard of in the past”. His family has also gradually accepted his career choice, after seeing him frequently appear in various news journals.

The more curious types have sent Chung messages on social media, asking if they could learn under his wing. “I can tell these people are sincere and not out to make a quick buck,” he said with delight.

Despite the progress made in recent years, the Hong Kong government still has much ground to cover in terms of demystifying death and the funeral industry, according to Chung. Compared to foreign countries and Taiwan, Hong Kong remains conservative in funeral matters and lacks its own learning system in the field.

It strikes Chung as ironic that in a city of such efficiency as Hong Kong, people have to wait so long for many procedures after death, such as cremations and funerals.

These existing challenges are adding new motivation to what the job of a funeral director means to him, said Chung, who has decided to stay in this industry for life.

“My ultimate goal is to train my students to become professional and trusted funeral directors, who can better serve the community, and to improve the public understanding of death and our industry.”

Extra Credits

Advisor Ting Shi

Editorial Director Hailey Yip

Multimedia Director Madeleine Mak

Multimedia Producer Feifan Yu

Photographer Zack Chiang

Copy Editor Jamie Clarke

Fact Checker Claire Kang