What Moves Stock Markets?

A Look at Hong Kong

By David A. Bruce

The market crashes! The market takes off! Where will the market go? All possible headlines reacting to stock market behaviour, but what does it mean and how is it measured?

The financial press keeps us informed on stock market movements on a daily basis, and also electronically in real-time. Individual stock prices are closely followed by investors, often leading to knee-jerk reactions to buy or sell. While various stocks can move in different directions at the same time, overall, stock market values either move up or down. Occasionally, they do not even move and remain steady.

In appreciating what moves entire stock markets, we need to understand the tools used to measure market performance – indices. Each stock market will report its performance using an index, and in some cases, more than one.

To explore the reasons why markets can move in unison, egging each other on and, at other times, unilaterally, we will consider three markets: Hong Kong, New York and London, with special emphasis on Hong Kong. For Hong Kong, we will monitor the Hang Seng Index, for New York the Dow Jones Industrial Average and for London the FTSE 100.

Key Indices

Hang Seng Index

The Hang Seng Index was launched in Hong Kong on 24 November 1969 with the base index of 100 being set to 31 July 1964. The number of companies included in the index has grown over the years and as of 4 May 2023, stands at 76. The index consists of the largest and most liquid stocks listed in Hong Kong. There are also four sector sub-indexes covering Finance, Utilities, Properties and Commerce & Industry.

Dow Jones Index

The Dow Jones, as it is referred to, was created in 1896 by Charles Dow to help him measure the overall market’s performance. The index consists of 30 large stocks covering major industries such as retailing, technology and finance. Over the years, the Dow Jones has reflected many world events, including moves from rail to air transport, the Great Depression, events of the Second World War and global financial meltdown.

FTSE 100 Index

The name of FTSE 100 reflects the two companies that introduced the index – the Financial Times and the London Stock Exchange. The index was launched in January 1984 and consists of the 100 largest companies by market cap listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE).

Looking at events over the last 30 plus years will help us understand why markets moved in the way they did. Specifically, we will look at: the events surrounding Black Monday 1987, when markets were in lockstep; August 1998 when Hong Kong was out on its own dealing with overpowering speculator attacks; and the contrast between SARS in 2003 and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008.

Out of the three markets, Hong Kong is very much the youngest, although it has had to grow up quickly. The history of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange is relatively short compared to those of New York and London.

The History of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange

The first formal stock exchange was created in 1891 with the formation of the Association of Stockbrokers in Hong Kong. The name was changed to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 1914 with a non-Chinese membership, reflecting the ever-present British colonial influence.

In 1921, a second exchange, the Hong Kong Stockbrokers’ Association, was formed with an all-Chinese membership. In 1947, after the Second World War, these two bodies were merged to create the new Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Rapid economic growth led to the establishment of three more market-driven stock exchanges.

1969 Far East Exchange

1971 Kam Ngan Stock Exchange

1972 Kowloon Stock Exchange

As noted by Hong Kong Securities and Investment Institute in its licensing examination study material for Paper 1, the market was planning to open several more exchanges by 1973. Given the lack of control over the activities of these exchanges, the government enacted the Stock Exchange Control Ordinance in February 1973 banning the opening of any more exchanges.

The operation of four stock exchanges lasted until 1986, when, in an attempt to strengthen market regulation, all four were unified to create the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (HKSE). Trading of the new exchange started on 2 April 1986 using a new computer-assisted system.

After the dramas of Black Monday 1987, there were calls for a reformation of the Hong Kong securities industry, which resulted in two major developments. In 1989, both the Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company was created to introduce a central clearing and settlement system (CCASS) for securities transactions and the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) was established as the single statutory markets regulator.

Finally, the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited was created in 2000 with the merger of the HKSE, the Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company and the Hong Kong Futures Exchange (HKFE).

Black Monday, October 1987

One of the most consequential global financial events affecting Hong Kong saw stock markets worldwide move in the same direction and time. Some would say that Hong Kong was by far the worst hit.

James Hogan began his banking career in Hong Kong two days after Black Monday. A fresh business graduate from Dublin, Hogan, then 22 and single, arrived with one suitcase and checked into the YMCA just around the corner from the HongkongBank’s training centre. The stock market crash of Monday 19 October 1987 had Hogan and many of his trainee colleagues wondering if banking was the right choice.

“It was a doomsday scenario for youngsters starting their careers,” he recalls.

Stock markets had crashed around the world, led by Hong Kong and followed by Asia, Europe and the United States. Under the direction of Ronald Li, chairman of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, the Hong Kong market failed to open for the remainder of the week, but all other exchanges continued as normal. When the Hong Kong market did reopen the following Monday, prices fell 33%, having endured an 11% fall the week before.

A man outside of the Royal Exchange after the economic impact brought by Black Monday.

(Source: Hulton Archive, Getty Images)

Ian Hay Davison, senior partner of a UK accountancy firm, was appointed to investigate why Hong Kong’s market was unable to deal with the heavy selling pressure. His findings exposed a lack of systemic stability, where one broker defaulting could result in a domino effect. There were also issues with market manipulation and deception.

Davison delivered a set of recommendations to the HKSAR Government in May 1988, which led to the creation of the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC), one of Hong Kong’s leading financial regulators.

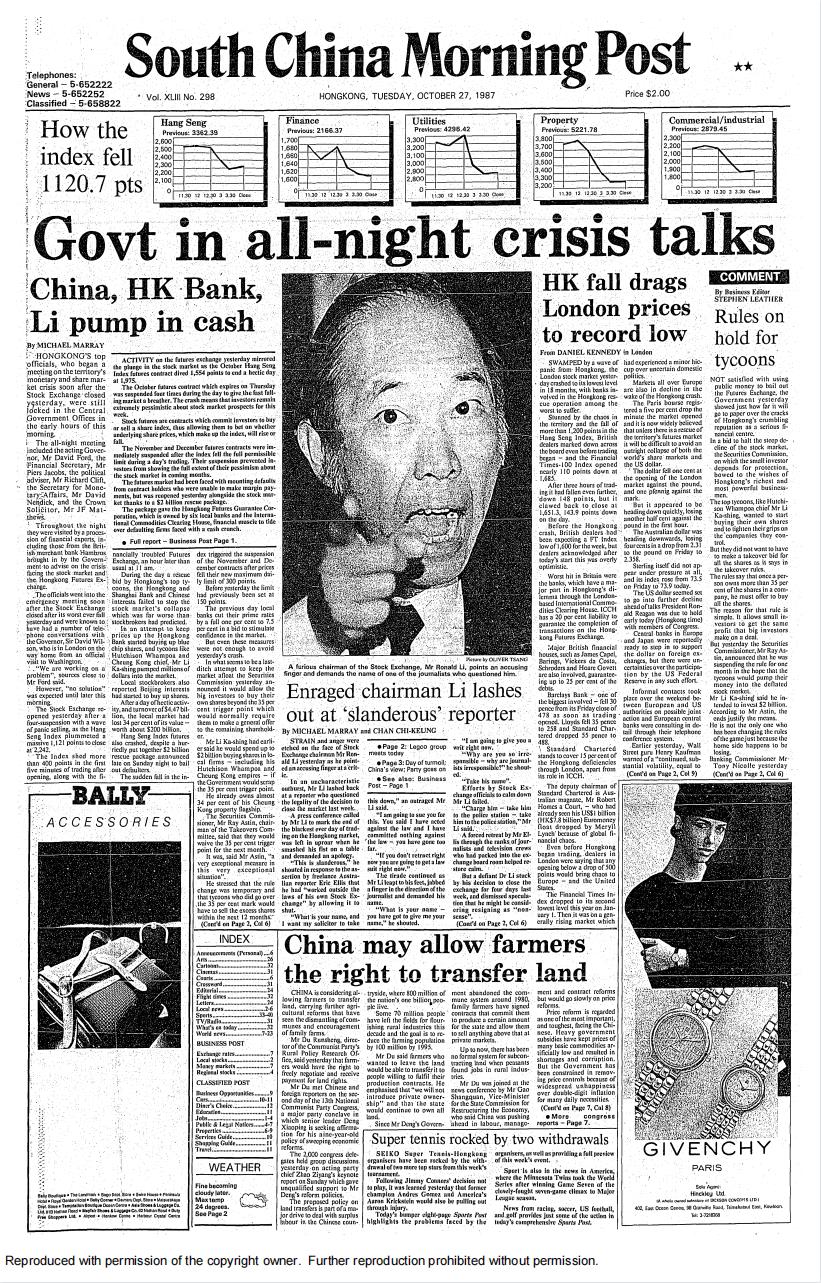

Interview of Ronald Li, the Chairman of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, after the crash.

(Source: South China Morning Post)

Many of today’s business graduates who are starting their Hong Kong financial market careers were not alive in 1987. During their licensing exam studies, they learn about the origins of the SFC without appreciating the events of Black Monday.

New York stock market prices fell significantly on the Thursday and Friday of the previous week, and the London stock market fell 5% on the Friday. In the U.K., the weekend press speculated whether or not prices would keep falling. They did. The global crash started in Hong Kong the next Monday morning and was followed by even deeper falls in London and New York — 11% and 23% respectively.

While a variety of stock investors were desperately trying to make sense of Black Monday’s market mayhem, the leaders of Hong Kong’s professional firms found themselves on the front-line, advising and protecting clients, while also steering their firms on a steady path through the chaos and confusion.

Stuart Leckie, 77, remembers a feeling of despair around town in the weeks following Black Monday. An actuarial consultant from Scotland, Leckie recalls clients asking if they should sell, hold or even buy. His advice focused on the long term, telling clients “do nothing, let’s see how things unfold.” His advice turned out to be sound. As he points out, “$100 invested in the Hong Kong market at the beginning of 1987 was worth around $105 at the end of the year.”

Source: Stuart Leckie

Sadly, investors who had borrowed money from brokers to buy stocks as they climbed in price, discovered that when prices reversed, brokers wanted their money back. Small investors with limited resources had to sell stocks at a significant loss to pay the brokers’ margin calls.

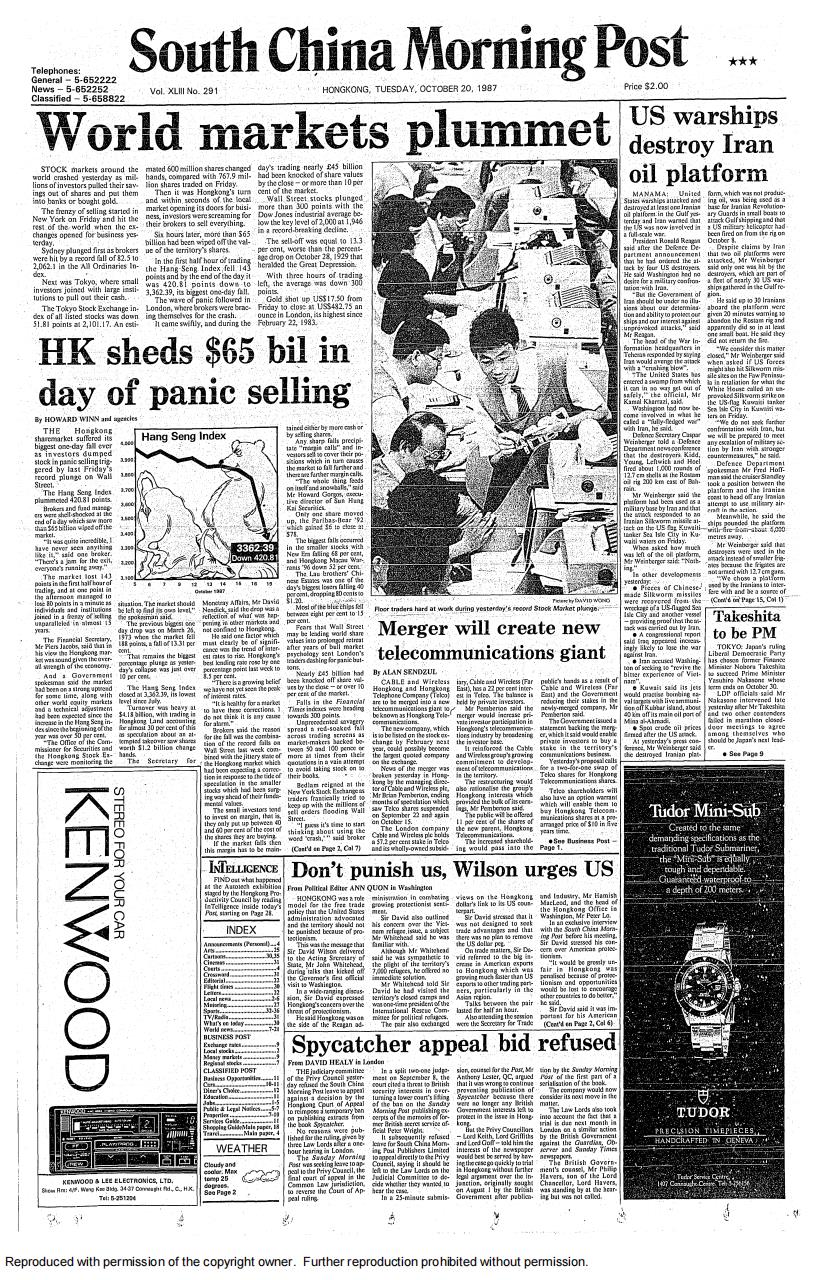

Dire impacts of the Black Monday event makes the frontpage. (Source: South China Morning Post)

David Lindsay, 67, a chartered surveyor from England, had invested in a selection of Hong Kong stocks prior to the crash. His investment was partly financed by a loan from his broker, a practice known as margin financing. When prices started to fall, his broker asked for the loan to be repaid. Lindsay did not have that sort of money and decided to sell his entire holding when the stock exchange finally reopened. He realised a loss of over $30,000.

“I felt pretty depressed for a while and a bit stupid,” he said.

Lindsay remembers that “everyone was in shock. It was a weird time.” Lindsay’s investment activities took a break for over five years to allow his Black Monday wounds to heal.

Traders read news about collapse of the global stock markets. (Source: Bettmann,GettyImages)

It was a different situation for Allan Zeman, 73, an entrepreneur who started in trading before moving into Lan Kwai Fong property. A canny investor, Zeman was wary of the stock market. “It was more of a casino back then. People invested on the basis of a company’s stock number. Very unsophisticated.” As the stock market fell, so did the property market and Zeman saw investment opportunities opening up.

“My entry into the Lan Kwai Fong property market was enabled by the Black Monday aftermath,” he said.

Frontpage report of the economic casualty brought by Black Monday. (Source: The New York Times)

Some professional services firms found business opportunities in the wreckage. Brian Stevenson, 77, was managing partner of an international accountancy firm. He recalls partner meetings when they analysed ways of helping clients navigate through the business challenges and, naturally, there was an increase in demand for liquidation services.

As Stevenson noted, there were opportunities in the Hong Kong property market, with property bargains popping up in Hong Lok Yuen.

Hong Lok Yuen is a low-density luxury residential housing estate in Tai Po and was developed between 1980 and 1993. In late 1987, Stevenson thought the stand-alone houses with their own gardens were selling at bargain prices. He told his partners about his discovery and three of them bought houses.

“As long as you are financially prudent, a crisis can present real opportunities,” he said.

This sentiment is emphasised by Roger Nissim, author of the 2020 book “The First Estates: The Story of Fairview Park and Hong Lok Yuen with Documents”. Nissim, 77 and a 50-year veteran of Hong Kong, chronicles the price movements in Hong Lok Yuen houses from 1983 to the present day. He shows that a 3,500 square foot residence that cost HK$1.9m in 1983 rose to HK$2.5m in 1987, but he concedes that market transactions post October 1987 fell way below the developer asking prices.

“When there’s blood on the streets, that’s the time to buy. Someone who can’t pay the mortgage, will sell low,” he said.

In 2023, those same residences were selling for HK$50m.

Hong Kong Under Attack, August 1998

From a Hong Kong perspective, August 1998 was all about naked short selling, in an attempt by speculators to bring the market down and to force the HK$ to delink from the US$. This was in line with other Asian markets earlier in 1997, when local currencies were forced to delink from the US$. The first in line was the Thai Baht in July 1997 when international speculators attacked the currency.

What is Short Selling?

Source: Simeng Xu

The Hang Seng Index fell 6.3% for the month, however at one point it was down 15.7% and then rose by over 20%. The speculators attempting to break the HK$ peg were stopped in their tracks during the morning of Friday 14 August when the Hong Kong Government instructed the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) to intervene and to start buying stocks in the open market. This resulted in prices rising immediately with many speculators withdrawing, nursing their significant losses.

The government intervention continued up to and including Friday 28 August, drawing condemnation from free market enthusiasts, including Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman and then US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan. However, as reported by CGTN, Greenspan acknowledged in 2008, at the time of the Global Financial Crisis, that the Hong Kong government had got it right and even George Soros admitted in 2001 that the Hong Kong authorities did “a very good job when they intervened to arrest the collapse of the Hong Kong market.”

Elsewhere in August 1998, the DJIA fell 15% and the FTSE 100 retreated 9.6%, reflecting market exposure to Russian political meltdown with President Yeltsin’s candidate for Prime Minister being turned down 3 times amid the prospect of a collapse in the Russian Rouble. Hong Kong had other things to worry about.

An unintended consequence of the Hong Kong Government’s market intervention was the creation of TraHK – the Tracker Fund of Hong Kong. As reported by TraHK, in September 1998 the HKMA was sitting on tradable stocks worth over HK$33 billion and had to consider how best to dispose of them without causing undue market disruption. Stuart Leckie, one of the government advisers at the time, remembers that “the government was keen to listen to market experts to work out what best to do.”

After taking on that advice, the TraHK’s Initial Public Offering (IPO) in November 1999 was the largest IPO in Asia ex-Japan (Asia excluding Japan), at the time. The fund continues to be considered a cost-efficient way of gaining exposure to the Hong Kong market, a positive outcome from a perilous time.

SARS vs Global Financial Crisis

A pre-cursor to the COVID-19 pandemic, which lasted from 2020 to 2022, was the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, known as SARS, that hit Hong Kong in March 2003. Although SARS reached other countries, Hong Kong was by far the worst affected. As stated in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, there were 1,750 cases identified between 11 March to 6 June along with 286 associated deaths. Although no lockdowns were imposed, few people travelled in and out of the city.

One of the SARS casualties was the stock market, which fell 5.5% in March 2003, while London, unaffected by SARS, fell 1.2%. Meanwhile, New York actually rose 1.3%.

Followed by the first confirmed SARS case in Hong Kong in Feb. 2003, Hang Seng index recessed in March, while SARS did not cause economic impact in New York. (Source: TradingView)

On the other hand, all stock markets were similarly affected by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) between mid 2007 and early 2009. The GFC was the result of a downturn in the US housing market which, in turn, led to many banks worldwide incurring large losses, with government bailouts required to avoid bankruptcies. The markets reacted in unison. From early November 2007 to February 2009, the Hang Seng Index fell 60%, the US market 49% and the UK market 43%. All three markets recorded their lowest prices at the end of February 2009.

The graphs show the stock market trend in Hong Kong and New York between the mid of 2007 to the beginning of 2009. Global Financial Crisis, started from the subprime mortgage crisis in the US, had caused recession to the stock markets around the world. (Source: TradingView)

Conclusion

As illustrated, stock markets can move together or they can stray off on their own reflecting local factors and influences. Black Monday is the best example of markets moving in unison, while Hong Kong’s unique market position is best reflected in the speculator attacks of August 1998 and the pressures endured during the 2003 SARS epidemic.

Hong Kong stock market mayhem has led to significant market developments on two occasions, helping Hong Kong rise up the international financial centre league table. The first was the creation of the SFC in 1989 as a result of Black Monday. As noted on its website, the SFC has continued to grow and develop since its inception, helping investors navigate subsequent financial crises, including the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the naked short-selling jamboree of 1998 and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

Ashley Alder, the SFC’s Chief Executive Officer from 2011 to 2022, noted in a 2020 Law Society interview that the SFC is focused on helping market participants deal with challenges and crises. The most recent issue at the time was COVID-19.

“We maintained close communication with licensed firms and industry associations to make our regulatory expectations as clear as possible during a critical time,” he said. “It is more important than ever that we stay focused on our core values and continue to deliver world-class regulation in the same way as we have always done.”

The second significant development was regaining international confidence by reversing negative sentiment from the 1998 government intervention. This was achieved by overhauling outdated legislation and introducing the Securities and Futures Ordinance in 2003. Since then, international confidence in the Hong Kong market has endured.

While the Hong Kong market previously aligned itself with global economic growth and development under the banner of globalisation, this may change significantly as the US and others attempt to decouple their economies from that of China. Predicting Hong Kong stock market performance going forward may no longer be linked to global factors affecting all markets and be more focused on factors unique to Hong Kong, as reflected in market reactions to local currency attacks and the SARS epidemic.

Forecasting the Hong Kong stock market may soon be less influenced by global factors.

Extra Credits

Advisor Diana Jou

Editorial Director Hailey Yip

Multimedia Director Madeleine Mak

Multimedia Producer Daoli Zhang & Wulfric Zhang

Illustrator Simeng Xu

Photographer Zack Chiang

Copy Editor Hugo Novales

Fact Checker Larissa Gao