By Leona Liu

HKU Journalism and Media Studies Centre

As an integral part of Chinese culture, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been practiced in Hong Kong for centuries.

Chinese herbal medicine can be found on the shelves of most local pharmacies, while herbal ingredients and restaurants are littered throughout the city.

Herbal tea stores can be found around Hong Kong (By Leona Liu)

Incongruous with a profound cultural background, only 7.2% of the residents in Hong Kong consult Chinese medicine practitioners, while nearly 85% of them subscribe to Western medicine only, according to a survey conducted by the Census and Statistics Department (CSD) last year.

Besides, as a city where East meets West, Hong Kong will see its first Chinese medicine hospital open in 2025, where the collaboration between Chinese and Western medicine in clinical practice can be realised on an institutional level.

Hong Kong Baptist University, the operator of the first Chinese medicine hospital, says the new hospital aims to serve as an exemplar of integration of Chinese and Western medicine. According to the city’s health minister, it will also strive to become a showcase for collaborative effort between Western and traditional methods to the world.

“The establishment of the Hong Kong Chinese Medicine Hospital is the culmination of a decades-long endeavour by the Chinese medicine profession. It signifies the establishment of a relatively complete healthcare system for Chinese medicine in Hong Kong,” said Chen Haiyong, assistant professor at the School of Chinese Medicine, The University of Hong Kong.

A flagship institution

Located in Tseung Kwan O, this hospital will be the first Chinese medicine hub in Hong Kong to provide comprehensive medical services to patients.

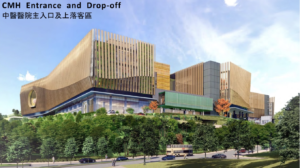

Chinese Medicine Hospital will open in 2025. (From HKBU website..)

The seven-storey building with 400 beds will offer both inpatient and outpatient services, enabling the use of instruments for physical examination, inpatient observation, clinical trials, and referrals, which cannot be achieved by clinics.

Under a public-private partnership model, around 65% of the hospital’s services will be subsidized by the government, marking progress during the integration of Chinese medicine into the public healthcare system, according to the Health Bureau.

This upcoming hospital will improve the city’s current TCM healthcare system which has only clinics and is mostly focused on primary health services such as the treatment of basic diseases, management of chronic disease, and health maintenance.

Traditional Chinese medicine in Hong Kong mainly provide primary health care services. (By Leona Liu)

The government reserved land for the hospital in 2014 and announced to fund HK$8.6 billion to build it in 2017.

With construction beginning in 2021, this hospital to be operated by the HKBU will be commissioned in phases starting with inpatient services first and then

‘Unsafe’ Chinese medicine

Milestone as the hospital is, why does it come so late?

Misunderstanding of Chinese medicine in Hong Kong society is one of the reasons.

Alan Koo, a Chinese medicine practitioner and owner of a private Chinese medicine clinic, said conceptions from the public and some Western doctors about the slow and harmful effects of Chinese medicine have prevented the development of Chinese medicine for years.

“Things could move faster than expected,” Koo said. “Even nowadays, you know, even when TCM becomes more popular, I still hear voices from Western doctors saying that, okay, TCM herbs can be dangerous, is unsafe.”

A string of incidents in the past that saw patients have adverse reactions to Chinese medicines may have contributed to the popular view that they are unsafe.

In 2011, there were even reports of four deaths due to poisoning by Chinese medicines and health products.

Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine from the University of Hong Kong said that about 33% of the Chinese medicine poisoning cases over the past 13 years involved excessive intake of alkaloids contained in Chinese herbal medicines. More than a quarter of the cases did not seek advice from Chinese medicine practitioners.

Data from the Hong Kong Poison Information Centre showed that the number of poisoning cases involving Chinese medicines hovered around 200 to 300 per year from 2009 to 2019, accounting for less than 10% of the total.

Skepticism about the effectiveness of treatment is another reason for the unpopularity of Chinese medicine.

“It’s actually one of the misconceptions that we always hear from patients when they have something acute. For example, they started to have a fever, they had a cough. They definitely go to Western doctors first to get some painkillers through,” said Koo.

A study conducted by HKBU in 2018 showed that 65% of citizens considered Western medicine to be more scientific than TCM, while only 12% were opposed to this idea.

The study also indicated that trust in health care is related to trust in the system governing it.

“The regulation of biomedicine and the dominance of biomedicine in the public health system in Hong Kong has been in place for 60 years. The regulation of TCM practices in Hong Kong was established only two decades ago,” said the study. “It is understandable that TCM will take some time to develop credibility and earn the trust of the public.”

Too long, too costly

Another factor that has hindered the official endorsement of Chinese medicine is its cost.

At present, there are around 10,000 Chinese medicine practitioners in private clinics in Hong Kong. In contrast, the city only has 18 public-funded Chinese medicine clinics.

According to a survey conducted by HKBU in 2018, a typical consultation with a private TCM practitioner is about HK$200, cheaper than a visit to a private Western practitioner which costs about HK$300, including two to three days of medication.

However, in Chinese medicine treatment, patients should pay a medicine fee and an “herb decoction” fee if they want herbs to be boiled or processed into liquid by clinics.

A typical fee for two to three days of medication with decocting is around HK$270, as the HKBU survey said.

Unlike Western treatments, Chinese medicine treatments are often done in more frequent sessions over a longer period.

Therefore, the final cost of treatment through Chinese medicine can be much higher than that of Western medicine, not to mention special treatments such as acupuncture, which costs around HK$500 for a single session.

The price of Chinese medical materials ranges from tens to thousands of Hong Kong dollars. (By Anna Wang)

“For the time being, Chinese medicine in Hong Kong has not yet been popularized among the general public, or the grassroots cannot afford to pay for Chinese medicine for a long time,” said Letitia Chan, a Hong Kong citizen in her 30s who has been trying TCM for over ten years.

“If the government provides subsidies, it may refund a portion of the fees to the patients every time, and in the long run, the burden of medical consultation on them will be much smaller,” she added.

In government-funded Chinese medicine clinics, all treatments are free for patients over 75 years of age and other subsistence allowance recipients.

For other patients, the consultation fee in a public clinic is HK$120, which includes up to five doses of medicine, while acupuncture and bone massage have also been capped at HK$120 per session.

However, due to limited services and quotas, these 18 public clinics are not enough to meet the needs of the citizens.

“Even though it’s cheaper to see a doctor at a government-funded clinic, most of the people I know still go to private clinics because we want to see a doctor regularly to get better health outcomes, rather than waiting for a quota to see a doctor,” said Chan.

Colonial legacy

The interruption of Chinese medicine development during the British rule is another reason for no presence of the CM hospital.

During the British colonial period, Western medicine had gradually replaced Chinese medicine as the mainstream.

enacted in 1884 by the then Hong Kong Government required only registration of Western medical practitioners and the use of Western medicines in the colonial city, while Chinese medicine was not subject to the regulation, according to a study from the Hong Kong Registered Chinese Medicine Practitioners Association (HKRCMPA). This meant Chinese medicine practitioners were not officially recognized medical personnel.

In 1905, the British Hong Kong Government’s legislation prohibited Chinese medicine practitioners from treating smallpox patients, and the status of Chinese medicine practitioners and their social status were further degraded, the HKRCMPA study says.

It would take another nine decades for Chinese medicine to be officially addressed.

Hong Kong Basic Law, which came into effect in 1997 when Hong Kong was formally handed over, stipulates that Chinese medicine have a legal status in the city.

According to Article 138 of the city’s mini-constitution, the HKSAR government “shall, on its own, formulate policies to develop Western and traditional Chinese medicine and to improve medical and health services. Community organizations and individuals may provide various medical and health services in accordance with law.”

Then the government enacted the Chinese Medicine Ordinance in 1999 to establish the professional status of Chinese medicine practitioners (CMPs) and started to implement measures to regulate the licensing of Chinese medicine practitioners and the use of Chinese medicines.

Compared with Western medicine, the ordinance for Chinese medicine has a simpler classification, and it’s easier to be licensed as a CM practitioner.

Western medical graduates need first pass the licensing examination, then undergo 12-month training and assessment in approved hospitals as interns, from which they will receive clinical instructions to familiarize them with the local medical system and commonly found diseases.

Chinese medicine practitioners only need to pass the licensing exam including written tests and clinical interviews.

In November 2002, the first batch of 2,384 CMPs completed registration, and in August 2003 the first CMP licensing examination was held, according to the Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong (CMCHK).

However, since the Hospital Authority (HA), the official organization responsible for the management of all public hospitals and related medical services in Hong Kong, was set up as early as 1990, Chinese medicine had been excluded from the public health care system in the form of clinics despite official status.

the past two decades, the government has subsidised several Chinese medicine clinics in their attempts to incorporate Chinese medicine into public healthcare. The first Chinese medicine hospital will be the long overdue next step.

A silver lining of the pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic offered a silver lining to Chinese medicine.

Over the outbreaks, Chinese medicine applications including the use of proprietary products in treatment and prevention came into effect in the city.

The government also provided recovered patients free rehabilitation sessions at public-funded CM clinics, with the help of attracting more residents to try out Chinese medicine.

According to a survey from the Census and Statistics Department (CSD), in 2015, among the 1.6 million persons who consulted a doctor during the 30 days before survey enumeration, 89% had consulted biomedicine practitioners, while 18% had seen TCM practitioners.

The gap has narrowed since the outbreak.

In the results from the CSD, the percentages of those who consulted Western medicine and Chinese medicine in 2023 were 80% and 24%, respectively.

Besides, according to a survey from HKBU, by 2022, almost 90% of the respondents believed that Chinese medicine could treat the epidemic, and 92% of them would seek Chinese medicine if there was little improvement in their symptoms after Western medical treatment.

Chan’s husband, Eric Lam changed his attitude towards Chinese medicine after the recovery from Covid.

“I have always felt that when I encountered very urgent symptoms, seeing a Western doctor would be more effective, but after my Covid healed, the cough became very serious, and I took a lot of Western medicine drugs.”

“It is felt that the mechanism of Western medicine is always just to stop coughing, but I found that seeing a Chinese medicine will help me to better regulate my overall health, after trying Chinese medicine treatments once or twice, I will not cough again,” said Lam.

Lam is a nurse at Kowloon Hospital, a public Western hospital in Hong Kong.

He had not tried Chinese medicine treatments before the pandemic because of concerns about costs and slow effects.

But now, joined by his wife, he changed the stereotype of Chinese medicine.

“I recommend my coworkers to see a TCM doctor if they are suffering from the aftermath of Covid. Because the virus can make a difference in your body, it’s important to treat the root cause. I think TCM does have its advantages,” Lam added.

Koo also said his clinic has welcomed more patients after the pandemic.

“So I think most patients have changed their paradigm or they changed their perspective to TCM. They are now more receptive and even have a reinfection of coughing. Now they come to TCM doctors first,” said Koo.

growing support for TCM paved the way for the government to greenlight the city’s first-ever TCM hospital.

“During the COVID-19 epidemic, Chinese medicine has played an important role through in-depth participation in the whole process of epidemic prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation,” said the Secretary for Food and Health, Sophia Chan, in a Legislative Council in May 2022.

Chan also said during the meeting that the government would further widen the application of Chinese medicine based on the sector’s development during the pandemic.

Chinese medicine plays a big role during the Covid-19 pandemic. (By Leona Liu)

In the 2023 policy address, the Chief Executive has pledged to come up with a blueprint for the development of TCM and create a position of commissioner for Chinese medicine development.

Speeding up the preparation of the first Chinese medicine hospital is also listed in the policy address.

An unprecedented effort

A final-year student in the six-year undergraduate program of the School of Chinese Medicine at HKBU, Guo Tianchen said the upcoming hospital will allow practitioners to be relieved of some of their limitations and make it possible for them to perform more complex diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

“ Chinese medicine hospitals, there is no right to Western medical examination such as X-ray and prescription of Western medicines, which has great limitations on the clinical diagnosis and treatment of Chinese medicine.”

Limited by the Ordinance, Chinese medicine practitioners in Hong Kong

currently do not have the right to instruct patients to undergo diagnostic

imaging tests and laboratory tests. This can restrict the CMPs’ diagnosis and

treatment, especially for orthopedics clinics.

Besides, Guo said this hospital can also be a good place for clinical teaching so that Chinese medicine students in Hong Kong will not have to intern in mainland hospitals as a graduation requirement.

Clinics have limitations in developing Chinese medicine. (By Leona Liu)

Koo added that current private clinics may also benefit from the hospital.

“It could help set the standards for private practice in Hong Kong,” he said, adding the public hospital could involve the private sector in terms of research of TCM education, continuing medical training for practitioners.

“There could also be lots of things happening between the private sector and the public sector,” Koo said. “For example, in the future, if we see patients needed, we can refer to that public TCM hospital for hospitalization, or that referral system will not be possible without the establishment of that TCM Hospital to do this.”

However, cooperation of the two healthcare mechanisms in a hospital still faces daunting challenges, given distinct knowledge systems of Chinese and Western medicine.

As Tang Fei, a Hong Kong lawmaker, pointed out at a Legislative Council debate on promoting the development of Chinese medicine last June, “It is not the case that Chinese medicine practitioners and Western medical practitioners are placed in the same hospital and then it is called the collaboration of Chinese and Western medical practitioners or the integration of Chinese and Western medical practitioners.”

He cited the example of cancer treatment in the Chinese medicine hospital in the future, pointing out that it was necessary to consider how practitioners would decide on the next step of treatment after obtaining the laboratory test results.

“Should the patients continue treatment with a Chinese doctor or be referred to a Western doctor for surgery because the tumor has not yet metastasized? Or is it a combination of Chinese and Western medicine? Or should it be decided by the patients themselves? All these are technical issues that need to be resolved,” Tang said.

Koo suggested that the government should set up a comprehensive referral system.

Patients suffering from cancer who come to the TCM hospital should be referred to a Western hospital for surgery, then they can return to the Chinese medicine hospital for post-operative rehabilitation and cancer control, from which TCM doctors can also make use of image testing to follow up the recovery of patients, Koo said.

The government launched an Integrated Chinese-Western Medicine (ICWM) service in 2014 at 8 public Western hospitals, where four selected diseases, including stroke, musculoskeletal pain, and palliative care for cancer. This collaborative team only works together to discuss treatment options for inpatients.

This year, the number of hospitals participating in the joint services increased to 26, while the illness covered remains the same.

The reporter attempted to contact the relevant hospital administrators at HKBU to ask for details about the integration of Chinese and Western medicine in the future hospital but did not receive a reply.

Guo, the HKBU medical student, said it would take a comprehensive hospital’s inpatient department to effectively integrate Chinese and Western medicine.

Such integrated services, which the new hospital intends to provide, can mainly use Chinese medicine treatment with association of Western medical devices, such as testing blood glucose and blood pressure for hospitalised patients or using Western medical devices such as ventilators to help sustain life.

Guo said this corporation model has been adopted in mainland hospitals.

During her internship in the mainland, she witnessed Chinese medicine doctors first using ventilator and rehydration fluids to maintain the vital signs of a patient suffering from Guillain-Barre Syndrome, an immune system disorder, and then adopting Chinese medicine to treat him.

“If pure Chinese medicine treats this disease, the patient may have died of an emergency before he gets better,” she said.

Associate Dean of HKBU School of Chinese Medicine, Li Min, said at a press conference in February, that Hong Kong collaborates with mainland China’s biggest Chinese medicine hospital, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

“So we learn from them. We also need to create, and establish the unique Hong Kong Chinese medicine hospital,” she added.

On April 30, HA said 20 Chinese medicine practitioners would be sent to mainland China this year to receive in-patient care training, aiming to prepare talents for the commissioning of the Chinese medicine hospital in 2025.

This programme will last for two years, with participants spending eight months in mainland Chinese medicine hospitals for clinical treatment and the remaining 16 months in Hong Kong public hospitals to explore collaboration between Chinese and Western medicines.

Professor Chen, from HKU, pointed out Hong Kong’s medical operational mode is distinctive vis-à-vis that in the mainland, which has been combining Chinese and Western medicines for many years.

“Chinese and Western medicines are indeed two different medical systems, and how to co-operate between these two systems is indeed a brand-new topic,” he said.

“There is no precedent on how to co-operate among Chinese medicine practitioners, Western medicine practitioners, nurses, and other medical professionals.”

“But as a Chinese medicine hospital, I think the collaboration between Chinese and Western medicines should be carried out under the leadership of Chinese medicine practitioners on the basis of mutual respect among various professions.”

Advisor: Ting Shi