The Unbearable Waiting Room in Hong Kong

By Karin Lyu Kaiying

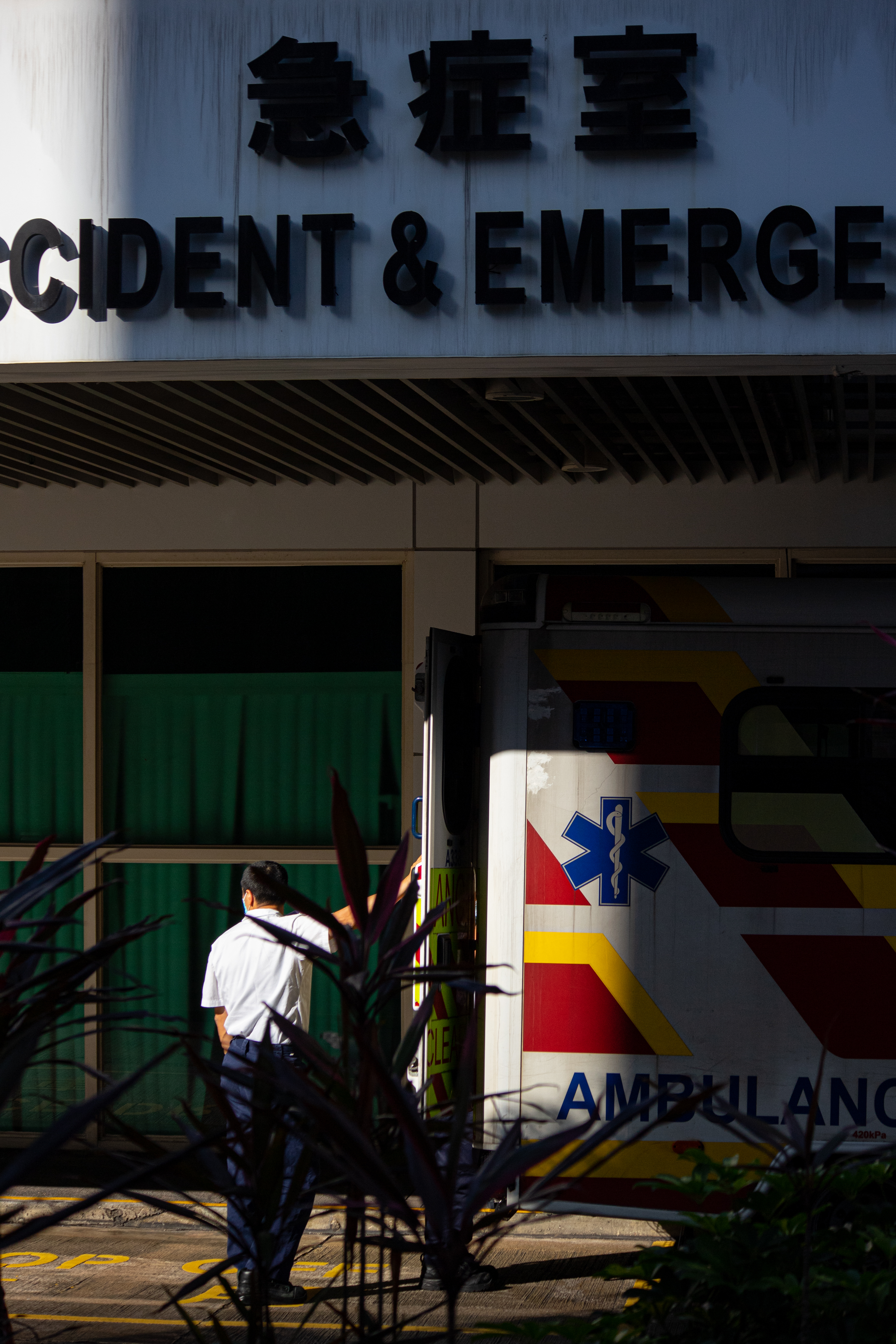

A 58-year-old female was found dead in a hospital toilet after waiting over 12 hours for treatment at a Hong Kong Island East emergency room on the afternoon of April 17.

Alex Lam Chi-yau, chairman of Hong Kong Patients’ Voices, said the woman’s death was avoidable, adding that her chance of survival could have been much higher if someone had located her earlier.

“It is an indisputable fact that the waiting time [in emergency rooms] has always been too long,” he said.

This is not the first case where a patient died in the emergency room; as recently as 2021, a 55-year-old driver tentatively diagnosed with acute liver failure died after waiting seven hours in Tuen Mun Hospital. Both incidents are a sign that waiting in hospital emergency rooms is becoming fatal.

People waiting at Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital emergency room. (Credit: Karin Lyu Kaiying)

According to our analysis of Hong Kong emergency room waiting time over the past year, long waits are becoming the norm rather than the exception. The proportion of waiting more than four hours in a Hong Kong public emergency room has nearly increased sevenfold between April 2022 (7.96 per cent) and April 2023, to 51.19 per cent.

The Hospital Authority releases updated wait times every 15 minutes of the 18 emergency rooms across Hong Kong. By analysing the collected 733,392 of these wait times from April 2022 to April 2023, the result showes that patients are waiting an unacceptable amount of time in the emergency room, leading to repeated accidents.

And this upward trend seems to be continuing.

Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, where the elderly woman died, is ranked seventh in terms of hospitals with longer-than-average wait times, suggesting that there are at least six other hospitals facing even more challenging conditions.

In the worst case, in 56 per cent of cases, patients at United Christian Hospital had to wait over four hours in the emergency room over the past year (April 2022 to April 2023). This figure does not include the waiting for any further examinations or specialist care.

According to a 2019 survey conducted by the Democratic Party Hong Kong, Hong Kong residents expressed dissatisfaction with public hospital services, with “long waiting times” cited as a contributing factor in 40% of the cases.

Aman Yiu, a 22-year-old American soccer player, waited around six hours for treatment at Prince of Wales Hospital, which ranks ninth for long waiting times.

Yiu said he was unable to move his right thumb and left index finger after they were injured during a tackle drill.

“Our emergency rooms are increasingly distant, and the waiting times are growing longer,” expressed Yiu. “While I acknowledge that it can be a challenging situation, I believe that this trend must be reversed.”

In response, the Hospital Authority emphasized that the triage system in public A&E departments is “efficient” and guarantees that patients with critical medical requirements receive timely treatment “within a reasonable timeframe.”

They added that during a “sudden catastrophic event,” the waiting time for patients “may be extended.”

The Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital said that they were in line with the Hospital Authority’s response, while the United Christian Hospital told us that the recent increase in COVID-19 cases has made the wait time “longer” and urged the public to consider other ways to seek treatment.

Yet the results of our analysis suggest that public emergency services may not be competent.

Hong Kong implemented the Triage System in 1988, which categorizes patients in emergency rooms based on the severity of their condition and the availability of medical resources, resulting in five categories. Each category determines the waiting time for patients.

The system has also been adopted in many other parts of the world, including the UK, Canada, and Australia.

At present, all 18 public emergency rooms across seven hospital regions in Hong Kong have implemented this system. Officials claimed that its purpose is to “facilitate the efficient allocation of staff and resources by directing patients to suitable treatment areas based on their medical conditions.

The National Health Service of the UK has pledged to ensure that patients receive timely treatment, that 95 percent of patients should be treated within four hours, also known as the “4-hour Accident and Emergency (A&E) target”.

Data from April 2022 to April 2023 reveals that the percentage of “excessive waiting times” amounted to 31%. This implies that for every three visits to a Hong Kong emergency room during that period, there was a likelihood of having to wait over four hours for treatment on at least one of those visits. According to the latest expenditure report submitted by the Health Bureau, there were a total of 1,963,000 A&E attendances in 2022.

With a 31 percent probability of patients waiting for more than four hours in emergency rooms last year, calculations (details provided in the sidebar) suggest that Hong Kong may only be able to guarantee that 70 percent of patients receive treatment within four hours. This falls short of the three-quarters target set in the UK.

Shortage of Doctors

In 2021, the Medical Registration (Amendment) Bill issued by the Health Bureau indicated that there were 2.0 doctors per 1,000 residents in Hong Kong. This figure is considerably lower than the doctor-to-resident ratios observed in Singapore (2.5), Japan (2.5), the United States (2.6), the United Kingdom (3.0), and Australia (3.8).

Given the population growth and the substantial turnover of healthcare workers, it is possible that this ratio may have declined further in the current year.

According to data released by the Legislative Council, public hospitals saw a loss of 486 doctors in the past year, resulting in a turnover rate of 7.7 percent. This figure represents the second-highest turnover rate in the past five years, trailing only behind the 8.1 percent recorded during the peak of the Covid-19 outbreak in 2021-2022. Interestingly, only 67 doctors, or 13.7 percent of the total, left due to retirement.

A survey commissioned by the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies (HKIAPS) in 2019, focused on job satisfaction among doctors in Hong Kong, revealed that over half of the doctors who had already left their positions cited workload as the primary reason for their departure. Salary and limited promotion opportunities were also significant factors considered by public doctors when contemplating leaving, with percentages of 48.1 percent and 38 percent, respectively.

Nurses dressing in front of the emergency room at Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. (Credit: Oliver Hu Runqi)

Among various departments, emergency rooms exhibit the highest doctor turnover, reaching as high as 11.0 percent.

The most experienced doctors are also leaving from public emergency rooms, with sophisticated Consultant doctors and Associate Consultant doctors accounting for 37.6 per cent and 35.4 per cent of departures.

However, as few as 510 doctors were admitted by the Hospital Authority in 2022-23, the lowest in five years.

The Hong Kong government is taking measures to address this issue. During a recent meeting of the Special Finance Committee, Hospital Authority Chief Executive Tony Ko Pat-sing announced that it was no longer mandatory for doctors to be proficient in Cantonese, potentially indicating a willingness to recruit more doctors by easing language requirements.

If more doctors had been available at the time, perhaps incidents like the death of the 58-year-old, who was not named by authorities, might be avoided.

Triage System to be Improved

According to the Hospital Authority, the woman went to the emergency room at Pamela Youde Nethersole East Hospital at 11 p.m. with a fever and cough.

She was seen by a doctor for the first time at around 11:15 a.m. the next day and was put on hold for further examinations.

After several unsuccessful attempts to locate her from 12.30 p.m. onwards, medical staff found her unconscious in the accessible toilet at 4.30 p.m..

She was pronounced dead after failed attempts to resuscitate.

The woman had waited over 12 hours to be seen by a doctor, and it took a further four hours for medical staff to find her once they had noticed her disappearance.

Authorities did not explain why it took so long to find her but stressed that hospital staff routinely check and clean these facilities seven times a day.

Emergency personnel take patient to the emergency room. (Credit: Karin Lyu Kaiying)

The Hospital Authorities have established a performance pledge for emergency room services, aiming to provide immediate treatment to all “critical” patients (Triage I) upon their arrival. Furthermore, 95 percent of patients categorized as “emergency” (Triage II) should receive treatment within 15 minutes, and 90 percent of “urgent” cases (Triage III) should be treated within 30 minutes.

However, there is no official commitment for “semi-urgent” (Triage IV) and “non-urgent” cases (Triage V).

Critics question the efficacy of this system as the woman in the Pamela Youde had been triaged as “semi-urgent” (Triage IV).

In a 2022 reply to initial questions from Legislative Council Members, the Secretary for Health said the average waiting time for semi-urgent and non-urgent patients was 100 minutes and 127 minutes. In 2022-23, these values jumped by 25 per cent and 26.8 per cent to 125 and 161 minutes, respectively.

By using “systematic and scientific” methods to assess patients’ condition, an “experienced” nurse will perform the triage work to prevent “deterioration and death”, according to the official description.

However, Tim Pang Hung-cheong, a community organiser from the Society for Community Organisation (SoCo) pointed out that the current triage system still has the potential for error.

Medical personnel carry a patient from an ambulance to the emergency room door at Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. (Credit: Oliver Hu Runqi)

“Depending solely on one experienced nurse to assess patient triage might not always be the best approach,” he explained. “Even though experienced nurses are deployed to emergency rooms, mistakes can still happen.”

“For example, some heart patients may feel dizzy after taking specific medications, which may be a sign of fatal brain diseases. However, they may be classified as an ‘urgent’ case (triage III) or even ‘semi-urgent’ (triage IV) if all other physiological indicators are normal at the time of triage.”

He said that hospitals should now focus on more “workable” improvements, such as developing accessible personal medical records to help nurses assess patients’ conditions accurately before triage, as well as monitoring patients’ vital signs after triage through additional manual or messaging equipment.

Overwhelming Patient Volumes

The influx of patients due to the onslaught of Covid and flu has also led to congestion in emergency departments.

In late April, officials said that each emergency room in the city is receiving more than 6,000 patients every day, an increase of nearly 40 per cent compared to the same period in 2022.

The rising patient volumes, combined with the falling number of staff, only puts more pressure on the system.

Matthew Tsui Sik-hon, the chairman of the HA Central Coordinating Committee (A&E) said, however, that most of these daily patients arrive with the flu or Covid and are not in severe condition at all.

“(In this case), if there are more critical patients at the same time, sub-critical or non-critical patients will have to wait longer,” he said, with an appeal to the public to go to general outpatient clinics or private clinics if their condition is not as serious.

People waiting at Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital emergency room with a screen showing a wait time of over 5 hours. (Credit: Oliver Hu Runqi)

According to a Health Bureau reply to the Legislative Council, from 2022 to 2023, 60 per cent of the around 1,963,000 visits to emergency rooms (1,176,900) were cases of “semi-urgent” (Triage IV) and “non-urgent” (Triage V).

Only 4 per cent, less than 80,000 cases, were labelled as “critical” (Triage I) or “emergency” (Triage II).

“A sizable number of patients who don’t really need such services should be the responsibility of primary care providers, but they make up the majority of attendances,” said another document (Hong Kong’s Current Healthcare System) published by the Health Bureau.

Abby Haai, a local resident, went to Queen Mary Hospital after a bout of acute gastroenteritis (a common infectious disease that can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain) and was not given an antiemetic injection (used to control the common effects of acute gastroenteritis) until five hours later.

She said it is normal for most citizens to choose to go to the public emergency rooms.

“Compared to the cost of clinics, which usually goes over $500, the emergency room is a cheap option,” she said.

A resident walking past the emergency room sign at Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. (Credit: Oliver Hu Runqi)

“But I don’t understand why everyone has to go to the emergency room lately when they get a minor illness like the flu. It’s apparent that you can get better by taking your own medicine!”

Hon Lam So-wai, a member in the Legislative Council highlighted the current poor promotion of primary healthcare in Hong Kong as a factor contributing to unacceptable emergency room waiting times.

“The government is not doing enough to educate the public about our medical systems,” she said. “I think they need to do more.”

Actionable Advice

After the patient’s death at Pamela Youde, the Hospital Authority announced that it would step up rounds and arrange treatment for abnormal patients in advance; those at higher risk would wait next to medical staff as much as possible.

However, the authorities did not give any guarantee of shorter waiting times.

During an oral questioning after the incident, Legislative Council Member Eunice Yung Hoi-yan stressed her disappointment with the government’s response.

“How many patients’ lives [do we] have to sacrifice to get a guarantee?” she asked.

Fortunately, our analysis can give us some possible solutions.

Most emergency rooms saw a significant increase in the probability of long waits after 8 p.m., followed by a plunge at around 8:45 a.m.

Data also shows a significantly higher frequency of long waits on weekend mornings (8:15 a.m.-14:30 p.m.) than on weekdays.

But even so, there’s no guarantee that visiting a hospital during these times will mean a shorter wait time.

Chris Chen, a 28-year-old basketball player, suffered a torn ligament in his right foot during training.

After arriving at the emergency room and enduring nearly five hours of waiting, he received the alarming news that his condition was severe and might require immediate surgery.

He asked the doctor how soon “immediate” would be, to which the doctor replied that “at the earliest” he could see a specialist within four weeks and then “with any luck” it would be his turn to have surgery in half a year.

“I might have learned to play wheelchair basketball by then,” Chen said with a shrug after finally having to return to the mainland for the surgery.

How We Analysed Hong Kong Hospital Wait Time Data

All 18 public emergency rooms in Hong Kong are part of seven hospital clusters. The Hospital Authority updates the waiting time for all emergency rooms on data.gov.hk every 15 minutes.

The waiting time is marked as nine other tags: “about 1 hour”, “more than 1 hour”, “more than 2 hours”, “more than 3 hours “, “more than 4 hours”, “more than 5 hours”, “more than 6 hours”, “more than 7 hours ” and “more than 8 hours”.

This analysis collected 704,070 wait time data from March 2022 to April 2023 and constructed tables by R in the temporal and spatial dimensions.

The four-hour time tag was crucial – it was an international benchmark that was used to gauge whether patients were being treated within the recommended maximum time. So the analysis defined more than four hours as “too long”.

The tables were combined with information on patient numbers, geographic location, and healthcare staffing provided by the Legislative Council, Hospital Authority and Health Bureau.

Analysis shows that the share of “too long” waiting time in Hong Kong emergency rooms stands at 29%.

According to the latest expenditure head submitted by the Hospital Authority, the total attendances of public emergency rooms in 2023 is 1,963,000.

Each patient has a 29% probability of experiencing a “too long” wait time during their visit to the emergency room.

To calculate the probability that 70% of the total attendances would receive treatment within four hours, we calculated the probability that less than or equal to 30% of the total attendances would receive treatment within more than four hours by using the “pbinom” function on the R programming tool. Essentially, the probability is the same for both, which is 99.48%.

The “pbinom” is a function used to calculate the binomial distribution, which outputs the probability of a particular event occurring less than or equal to a particular number of times in the total event P.

For example, it could calculate the probability of getting 26 or less heads from 51 tosses of a coin.

This suggests that almost all emergency rooms in Hong Kong fail to meet the British target, the only exception being the one at St John’s Hospital on Cheung Chau Island, which has a population of only 23,000.

Extra Credits

Advisor Cezary Podkul

Editorial Director Hailey Yip

Multimedia Director Madeleine Mak

Multimedia Producer Daoli Zhang

Illustrator Simeng Xu & Wulfric Zhang

Copy Editor Jamie Clarke

Fact Checker Claire Kang